Histories of Reportage

Thomas B. Allen: Artist of the Heartland

I first read about Thomas B. Allen (1928-2004) in Nick Meglin’s definitive book of interviews with reportage illustrators “On-the-Spot Drawing.” Allen’s words resonated with me:

“The only sacrosanct rule of art to me is personal involvement. An artist must be intensely involved with a subject in order to give it his particular insights and convictions—his point of view. If (an artist’s) involvement remains intense, the work will be as valid and honest. Without total involvement it wouldn’t be art, only pictures.”

Allen was born in Nashville, Tennessee and educated at Vanderbilt University, and at the Art Institute of Chicago. He began a successful career as a commercial artist in the 1950s, creating hundreds of illustrations for major magazines. By the 1990s, he illustrated more than 30 children’s books.

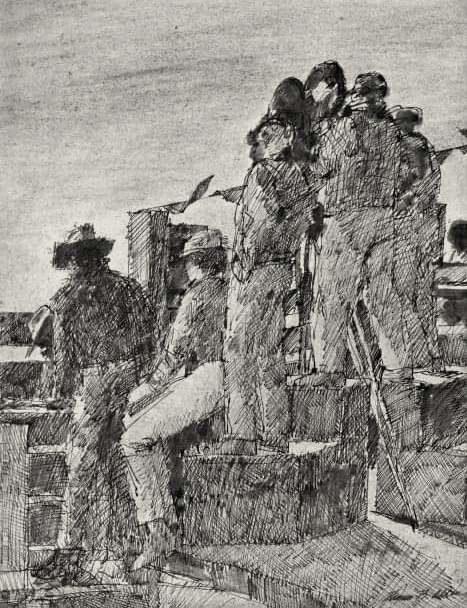

On location drawing by Tom Allen of a salvage operation for the Aquanauts television show, 1963

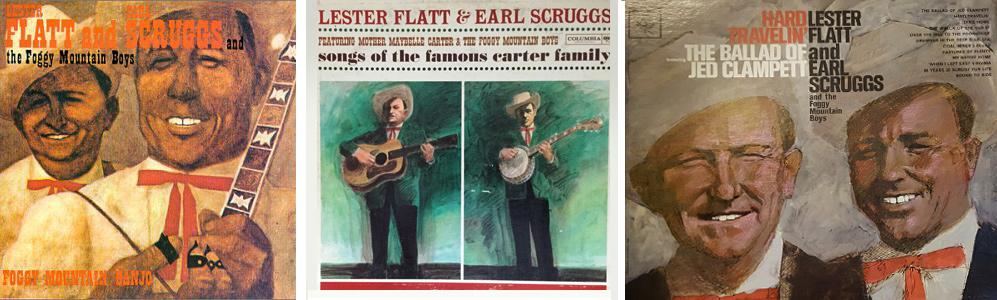

Allen gained a reputation as an artist with a homespun (read: timeless) quality to his work. He found his niche in the heartland of America, taking commissions with subjects like football rivalries, cowboy culture and traditional music. Allen created cover art for several albums of the bluegrass music of Flatt and Scruggs.

Flatt and Scruggs album cover art by Tom Allen

But his passion was to be “in the field.” Art directors at Sports Illustrated and Fortune magazine knew that by commissioning him, they’d get an artist who would fully commit to their reportage projects, as an artist-journalist. Allen brought his skills in picture making and an ability to create dramatic effects through the tonal variations he achieved with a pencil or a pen.

Drawing by Tom Allen of the rodeo set of the film ‘The Misfits’, 1961

There were times when his seemingly facile drawings didn’t come as easily. He shared…

“What’s not there is accomplished by struggle and accident rather than by design. Sometimes I’d scrub and scrape and practically destroy the paper (I was working on). When drawing on-the-spot, I know I’ve reacted emotionally to the subject and summoned the courage to begin (again, if necessary).”

Allen’s reportage held a sensitivity of person and place. Even back in his studio he’d rework drawings with a verisimilitude that was emotionally compelling and remained true.

Throughout his career Thomas B. Allen shared these abilities as a passionate teacher at Parsons School of Design, School of Visual Arts, the University of Kansas and Ringling College of Art and Design.

Obituary in the New York Times by Steven Heller

Paul Hogarth: Artist, Journalist, World Traveler

Leaping from sketching in the field to journalistic reportage often requires courage and collaboration. Courage to integrate oneself into the people and the moment. Collaboration by incorporating text or prose to the benefit of the story.

One who had both traits was the English artist Paul Hogarth (1917-2001). As the author of more than 20 books based on his travels around the world, he drew and put the people he met into his compositions with an exacting eye and an empathetic heart.

He was a writer in his own right, but Hogarth collaborated with several eminent authors, most notably Brendan Behan, one of Ireland’s greatest authors. Their books about Ireland and New York are steeped in reality and nostalgia, through Behan’s words and Hogarth’s images of these people and places.

Brendan Behan’s Island: An Irish Sketch-book tells us about what it means to be Irish. But it’s Hogarth’s complimentary drawings of girls of Limerick, storytellers of the Gaelic culture on the Aran Islands, and Dublin brewery workers that complete this rich narrative.

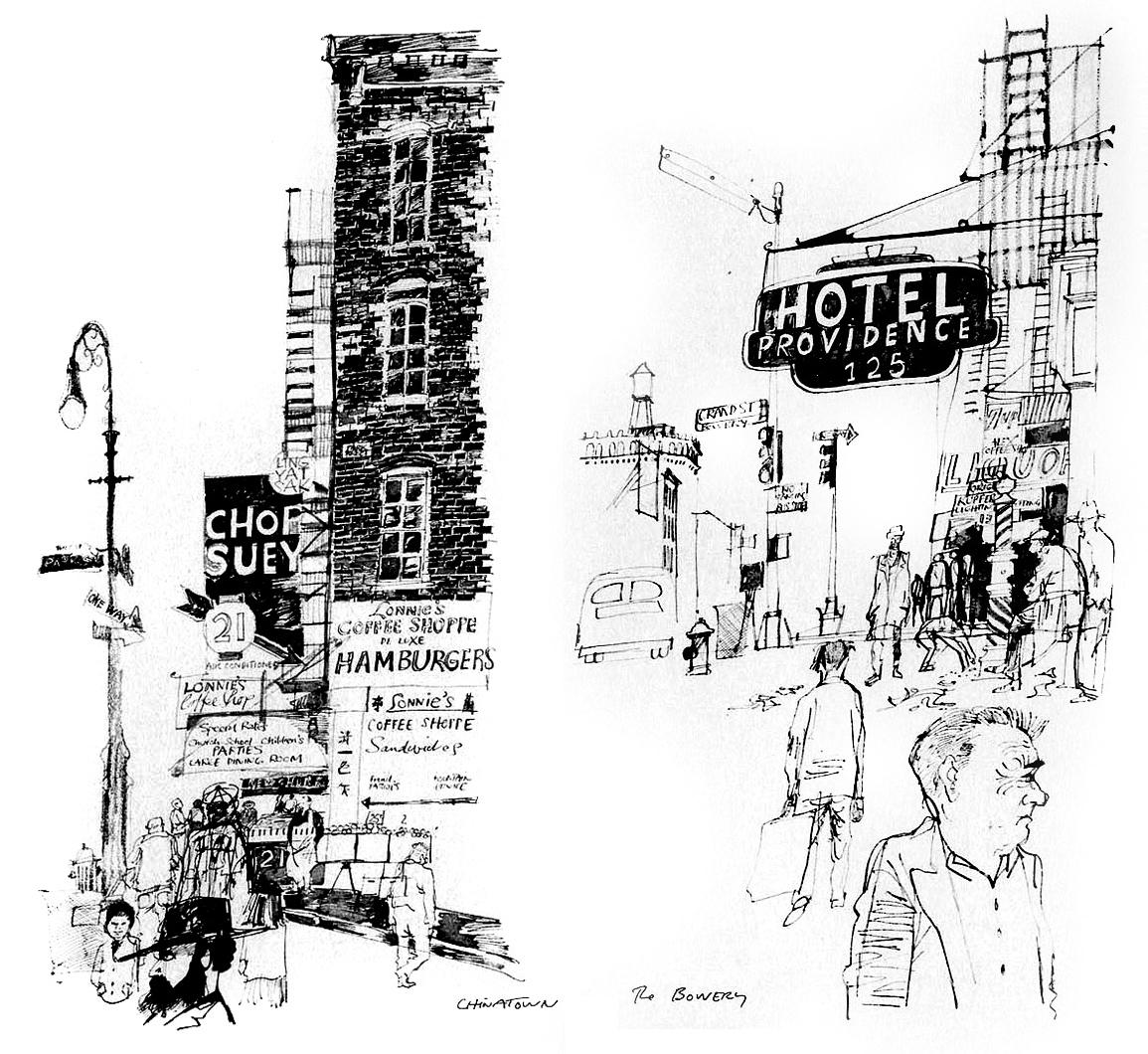

In Brendan Behan’s New York Hogarth travels to and draws a saloon on Third Avenue, a crowded beach at Coney Island, and the tenement complexities of Spanish Harlem, with authenticity.

Paul Hogarth is also a teacher we can learn from. His sketches educate and inform with the depth of a savvy storyteller. Read more about his brand of reportage in his book The Artist as Reporter.

Chinatown and The Bowery from Brendan Behan’s New York © 1964 Paul Hogarth

Ronald Searle’s War Drawings

Reportage artists attempt to bring experiential moments into their drawings. But what if these experiences seem too painful to draw?

British illustrator and cartoonist Ronald Searle (1920-2011) is probably best known as the creator of the St. Trinian’s School cartoons and his humorous fat cat illustrations. I discovered his work in the animated end credits he created for the movie “Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines” (1965). To me, the line work in his drawings holds both whimsy and angst, qualities he put to effective use as a prisoner of war in World War II.

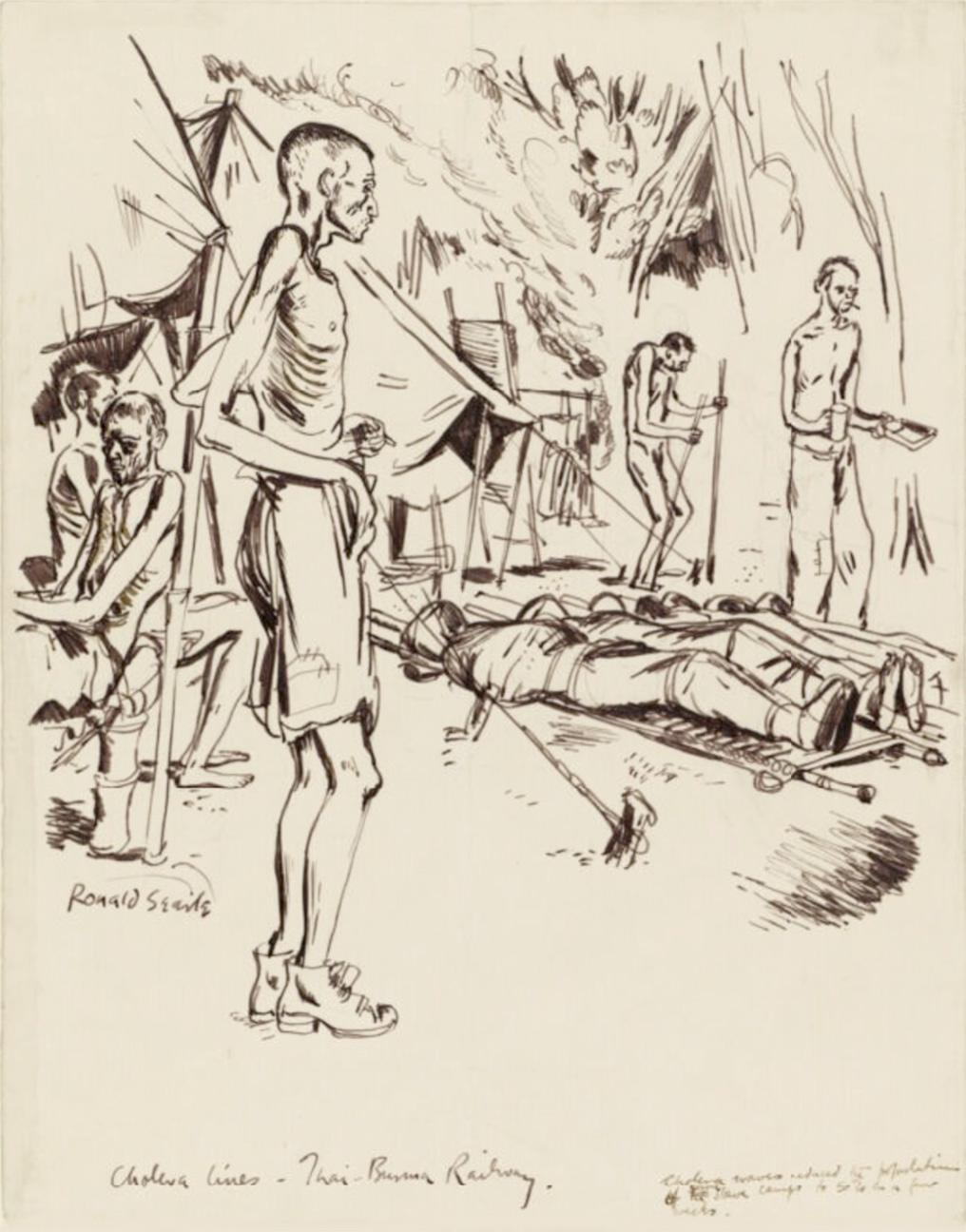

In 1942, as a soldier in the British Army, Searle was sent to defend Singapore. Soon after the Japanese conquered the city, he was captured and taken to the Changi Prison Camp as a POW, where he was forced to work on the notorious Siam-Burma Death Railway. Through three and a half years of brutal imprisonment, Searle found a purpose. He made drawings. He managed to obtain pens, ink and paper and secretly drew eyewitness reports of life in the camp, the dire working conditions his fellow soldiers endured and even made a few portraits of Japanese officers.

In 2010, Searle told The Guardian:

“I desperately wanted to put down what was happening, because I thought, that if by any chance there was a record, even if I died, someone might find it and know what went on.

At times I was so ill, I couldn’t draw at all. You’re doing 16 hours a day rock breaking and you’re exhausted. You come back and have a bowl of rice. You have no light, but you have a fire, to keep the mountain lions and snakes away. But by the light of that fire, I made the drawings.”

Sick and Dying: Cholera Lines, Thai-Burma Railway, 1943. Malnourished and imprisoned soldiers stand around bamboo stretchers lying on the ground, each containing the corpse of a cholera victim tightly wrapped and bound in a cloth at the Changi Prison Camp. Source: Imperial War Museums

If Searle’s drawings had been found, they would almost certainly have cost him his life. He kept them hidden from the enemy, at times under the beds of sick and dying cholera victims, in the hope that fear of the disease would keep Japanese soldiers away from discovery.

Searle’s reportage is a bleak and masterful record of the brutal camp conditions. His experiences and many drawings are compiled in his 1986 book, “Ronald Searle: To the Kwai and Back, War Drawings 1939–1945.”

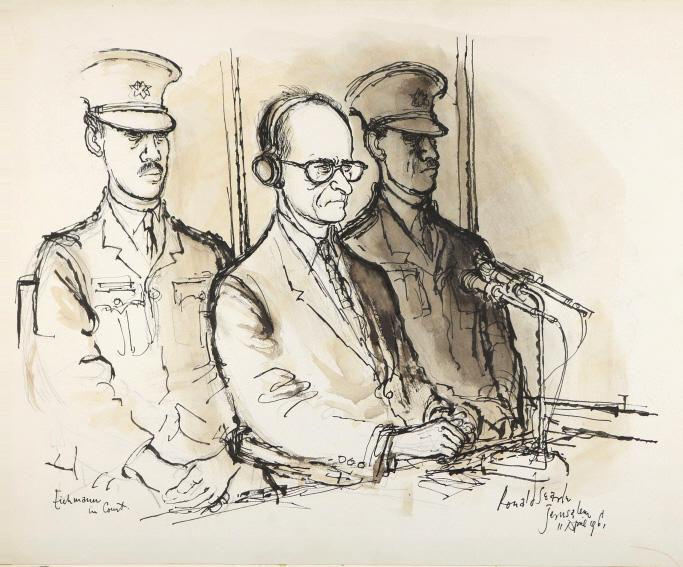

Searle never lost his skills of acute observation and dramatic storytelling. In 1961, he was commissioned by Life Magazine to cover the trial of former SS Officer Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem.

Gestapo Officer Adolf Eichmann on trial, 1961. Source: WikiCommons

- View an online archive of Searle’s war drawings at London’s Imperial War Museum.

- Read the complete story at the Illustration Chronicles.

- Read this ongoing tribute to Searle by artist and animator Matt Jones.

- Ronald Searle’s America is a compilation of Searle’s reportage in the U.S. in the 1960s.